There are few bona fide heroes in this world. Ones that genuinely inspire and continue to do so and who’s experience and accomplishments give them an unquestionable sovereignty of voice within their realm. And it’s not just that – they belong to a unique club characterised as the original trail blazers, the ones who set the precedent and the ones who shaped the industry – and the landscape – by playing their part in defining it.

One such person is John Lloyd who, as the front page of his remarkable online archive will tell you “…there are lots of John Lloyds on the web. I am the graphic designer who co-founded the international design consultancy, Lloyd Northover.” Quite a remarkable statement to lay claim to; the essence of which is humble, elegant, both perfectly encapsulating the soul of the not insignificant work of the man it seeks to introduce, yet still belying the substance of it.

I have a few heroes, each for unique reasons and I’m discovering new ones all the time (that’s why we started DJ after all), but a career spanning 50 years, numerous accolades, achievements, awards and work that has both endured and defined, quantify John Lloyd, who, in 1975 co-founded Lloyd Northover with former classmate Jim Northover (pictured right), as a design hero with true pedigree. We were lucky enough to chat with him…

DJ: You’ve designed some incredibly enduring identities during your career, of all, could you single out one that you still find particularly satisfying on the eye?

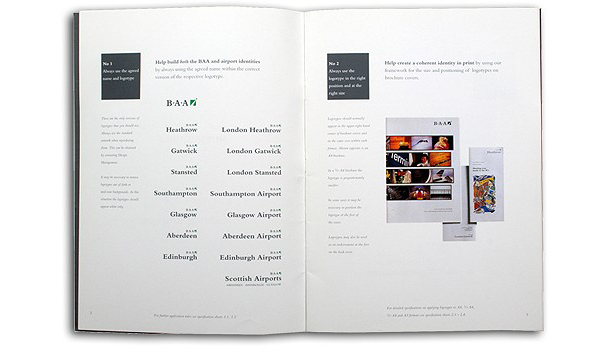

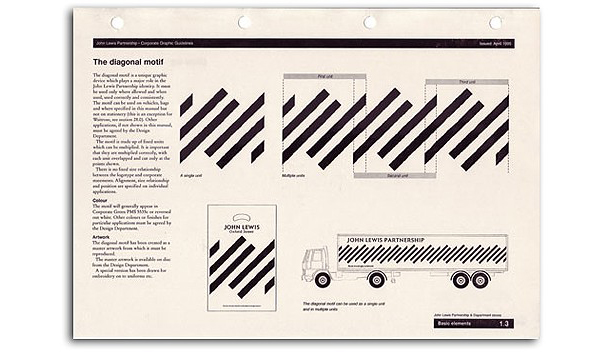

I think the symbol we created in 1986 for BAA (British Airports) is the most visually satisfying. I still like it for its utter simplicity. The three unadorned triangles constitute a symbol that immediately evokes airport activities and aviation but is clearly not an airline brand. The flexible identity system we created for the British department store chain, John Lewis, also pleases me. If you look closely, you will see that the diagonal pattern is not simply a series of diagonal lines but consists of a carefully designed module that can be repeated to create a mark of any length or size for use on the smallest ticket to the largest truck side.

DJ: In your formative years, did you have a mentor and did you receive any advice that particularly stuck with you?

I’ve had a few mentors. When I was an apprentice artist in the printing industry, I worked under a master called Ranald Woodward, who taught me diligence and attention to detail. As a student at the London College of Printing I learned not to have preconceptions and to use chance and random techniques to liberate creativity. I remember that one of my tutors, Eph Cowan, often urged me not to rest on my laurels, and I’ve tried to act accordingly. James Pilditch was one of the founders of Allied International Designers where I worked before setting up Lloyd Northover. He was one of the first people in Britain to take corporate design into the boardrooms of industry. From him I learned that corporate design is an important business and management tool; that it embraces not just graphics but products, environments, and behaviour; and that it is essentially about effectiveness and the achievement of results.

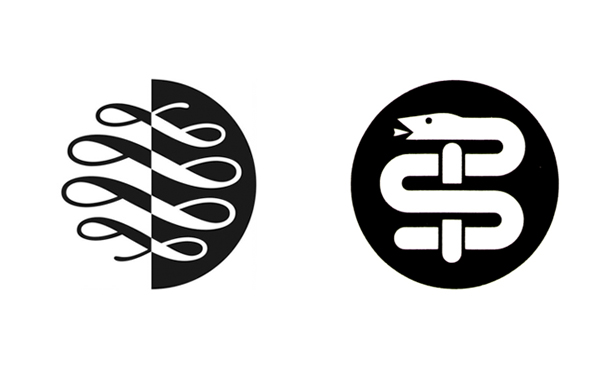

DJ: How do you see mark-making it and what process do you go through to create and refine an identity?

Corporate identity is, of course, about much more than symbols and logos but it is, more often than not, the core mark that distils, encapsulates, and expresses the nature and identity of the organisation. I believe that to do this effectively, a mark has to be simple, timeless, and easy to memorise. And, the best way to achieve a mark with those qualities is through a process of refinement and reduction.

DJ: When going through that process of creating an identity/brand, how were you able to judge whether the solution you’d created was right or appropriate in your earlier years before experience took over?

I have always studied the work of designers I admire to discover what makes a particular solution work so well. Saul Bass, Paul Rand, Chermayeff & Geismar, Massimo Vignelli, and Armin Hofmann, among others have, in many ways, been distant mentors. And, I have, over the years, avidly scrutinised the great design magazines: Graphis, Gebrauschgrafik, Print, Communication Arts, and Idea. As a kind of quality control, I would find myself thinking ‘now, how might Saul or Armin have tackled this?’

DJ: Did your approach evolve as you career went on?

We all learn from experience but my fundamental approach hasn’t changed: the striving for elegance, purity, and effectiveness have always been objectives. But, I have learnt a lot of practical things from a lifetime of implementing identities in all media – print, signs, environments, liveries, products, and digital. In this sense, my approach has become more pragmatic. I have also learnt that the greatest skill a corporate identity designer can acquire is the art of listening.

DJ: What culture did you try to impress on the younger designers that came to work under you?

At Lloyd Northover, these were our working principles:

Solve the client’s problem not your own: A brand should reveal the truth and essence of an organisation or service. Corporate design is about communicating the client’s identity, not your own. It has nothing to do with a designer’s self-expression.

Keep it simple: Creativity in design it is not about being crazy, wacky or ‘off the wall’ for its own sake. To be effective, a visual identity needs to be distinctive, legible, timeless, identifiable at a glance and memorable. The best designs achieve these aims through simplicity and clarity of form. Good corporate design is about achieving objectives through clear thinking and with the greatest economy of means. Unnecessary complexity indicates woolly thinking masquerading as creativity.

The best idea wins: Be consensus-oriented and encourage teamwork. Discourage individuals from ‘owning’ solutions. The objective should always be to find the right answer, and it doesn’t matter who has the idea, as long as it is the best solution.

Don’t rely on the computer: Computers can restrict the creative process. Use other media – drawing, painting, collage, photography – to stimulate ideas. Get out of the studio and look around. Try techniques involving randomness and chance. A designer needs to present himself with as many alternative options as possible from which to develop the most effective solution.

DJ: Having kept a relatively low profile throughout your formative years, the John Lloyd Archive is quite an extensive collection of work and a superb educational tool – what do you hope people will take from it?

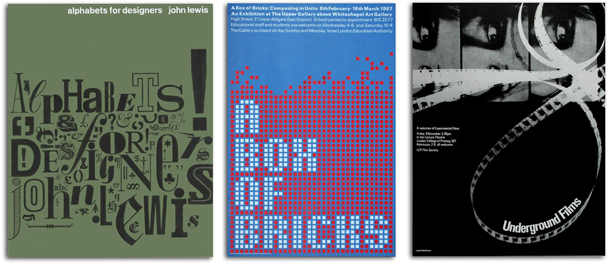

The full range of what Jim Northover and I did together, and the quality of our work, was only occasionally promoted by us and, therefore, never fully appreciated. Much of my early work, too, has not been widely exposed. Graphic design is ephemeral; it is easily lost and forgotten and by publishing the archive I wanted to ensure that the work survived. After fifty years in the profession, and as an examiner and visiting educator at design schools, it occurred to me that the archive, which spans the decades from 1960, and includes some ground-breaking and influential projects, should be preserved. I hope it will be seen as a useful contribution to the developing history of British graphic design.

DJ: Do you think younger designers can learn from identity work that was created before computers were used extensively?

Yes. The fundamental principles of what makes a good corporate identity remain the same, irrespective of whether solutions are drawn by hand or by computer, or whether communications media are traditional or digital.

DJ: You’ve said Saul Bass was a tremendous influence on your work, what was your connection to him prior to inheriting his Bass Yager studio after he passed.

I first came across the work of Saul Bass when I saw the titles for the films Carmen Jones and Psycho in my local cinema in the 1950s and 1960s. The various magazines I found in the LCP library introduced me to his corporate design work, which I greatly admired for its directness and freshness. I only met him once, and that was, much later, when Lloyd Northover designed the programme for ‘Transatlantic Shoptalk’, a conference of prominent US and UK designers at which Saul spoke. I never got to know him personally, but the influence of his approach was always with me. So, when, after his death in 1996, his business partner, Herb Yager, offered Jim Northover and me the opportunity to merge Lloyd Northover with the surviving Saul Bass practice in Hollywood, we accepted enthusiastically.

DJ: What was that experience like?

I remember, shortly after the merger, walking into Saul’s office on Sunset Boulevard. Many of his favourite images and examples of his work were still pinned to the cork wall behind his desk. It was as though he had stepped outside for a second and I found it quite an emotional moment. Although, I never had the chance to work with him, I did get to know, and work a bit with, Saul’s colleague, Jay Toffoli, who had participated as a designer in many of Saul’s great identity programmes.

DJ: How did you find Lloyd Northover’s move into Asia in comparison to your work in the UK and Europe.

We found that the Asian approach to corporate identity design and implementation was very compatible with our own. Our first project in the region was a major branding and implementation programme for the Airport Express in Hong Kong. We set up an office in Hong Kong and went on to develop the identity of the entire Hong Kong mass transit system. The next step was to open up in Singapore as well, where we created an island-wide branding and information system for the Land Transit Authority. We found that our clients in Hong Kong and Singapore were exceptionally well organised. They were very familiar with huge infrastructure projects and, consequently, their tendering and project management processes were highly sophisticated. Once a contract was agreed, with its milestones and deliverables clearly defined, everything worked efficiently, as it tends to do in Northern Europe.

Interestingly, we had much greater affinity with the Asian way of doing things than we did with the corporate cultures we found when attempting to work in the Latin countries of southern Europe.

DJ: The influence of technology aside, how would you say branding is different now to say 20-30 years ago?

It’s hard to put technology aside because so many brands today exist primarily in digital form. We are all familiar with the big ones: Facebook, Twitter, Google, Amazon and so on. But, there is also a multitude of smaller online businesses that barely have a physical presence and clamour for attention through the small screens of digital devices. The broad principles of what constitutes a good brand remain the same, irrespective of media, but it is increasingly important to make sure that a brand is designed to be highly effective in the digital environment.

Another major difference between now and the way that branding was developed 20-30 years ago, is the rise of design management. In 1975, when we started Lloyd Northover, it was usual for working relationships between client and designer to be close. Client’s took designers into their confidence and treated us as partners. Now, there is often a buffer between the client and the designer – a professional design manager. Bidding and selection procedures have become much more formulaic – the designer may be kept at arm’s length, and I fear that the relationship of trust between client and designer is being eroded.

DJ: Since retiring, do you still keep an interested eye what’s going on in the industry?

Yes. I read a lot, think and write about corporate design, and I have stayed pretty close to trends in design education, mainly as an external examiner. When you have spent a lifetime as a designer, it’s second nature to look at everything around you. I’m making new discoveries every day.

DJ: What do you make of the ‘new wave’ of design studios and the brands they’re creating and who do you see as today’s standard bearers of marque design?

The really big commissions still tend to go to the really big long-established consultancies. But branding is changing in that it’s much more about tribalism, belonging, and fluidity; consumers own and define brands as much as brand-owning corporations. Branding isn’t about one-way communications; it’s about engagement. It isn’t just about a share of the market; it’s about a share of the mind. The democratic digital networking channels play a key role in this. It’s easy for designers to be seduced by the technology; there is a tendency for too many visual gizmos to get in the way of crystal clear brand presence. Clarity should still be the name of the game.

Because the profession has grown so large globally, and become so fragmented, it is not easy to single out new standard-bearers. Nevertheless, a few influential champions of corporate identity design do spring to mind. David Airey, for example, practices as a brand designer in Northern Ireland, but also blogs and writes books on the subject, and influences a huge following; Tim Lapetino and Jason Adam of the design consultancy Hexanine, in the US, do likewise; while the American writer, Seth Godin, explores and promulgates new ways of thinking about marketing, branding and brand loyalty.

DJ: Having been involved in design education and with so many Graphic Design Degrees being offered these days, do you have any thoughts on how young designers can forge themselves in the industry?

The structure of the corporate design industry is changing. The days of the massive corporate identity consultancies with large teams of designers gathered in one place are on the way out. In the future, there will be fewer jobs in large design firms. Technology allows people to work at a distance in virtual offices and teams. And, experts will, when necessary, come together for specific projects, and then disband, as, for example, is the norm in the movie business. The important thing is to try to work on significant projects with the very best people in the field, and to make sure that the profession as a whole knows about you and your contribution. If your peers know and respect you, your fame will grow, and the work will come. If you are a good designer, I think the future is bright.

DJ: Is there any piece of work you’d like to revisit and refresh today?

The John Lewis identity has been tweaked by others, and not always for the better. I’d like to put that right.

DJ: What project, would you say, typified your career output or you found the most rewarding? Would you describe it as your legacy to the world?

There isn’t a single project that does that. I think my archive as a whole typifies my career.

DJ: Are you working on any projects at the moment?

Yes. I am working on a book about the very long history of corporate identity. And, I always have a painting on the go!

–––

We’re very grateful to John for sparing the time to talk to us, it is a genuine privilege. Time spent absorbing the John Lloyd archive, and digesting his reflections, can do no designer any harm at all. See the incredible work Lloyd Northover continue to produce here.